But although the sheep goes dumb to the slaughter, do not its [sic] eloquent eyes appeal for mercy? Do not the bleating of the calf, the bellowing of the bull, the cackling of the frightened geese, the gobbling of the reluctant turkeys, and the cries of the hundred of other creatures that we call dumb, but to each of whom nature has given its [sic] characteristic mode of speech, rise in eloquent protest against the savagery to which the instincts inherited from our cannibalistic ancestors habitually lead us? That we are able in cold blood to take the lives of these innocent beings, then to bury their carcasses in our stomachs, as do the savage beasts of the forest, is made possible only by the fact that the ancient savage still leaps and yells in our hearts. (Kellogg 1923: 219-220).

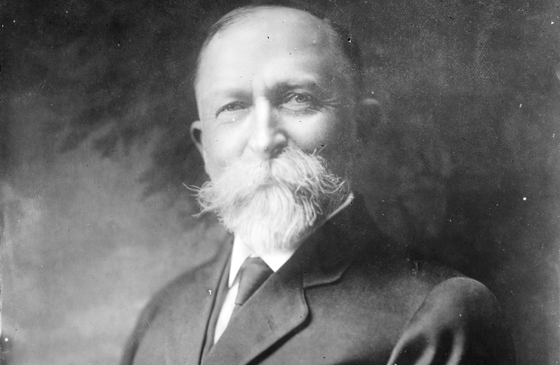

Dr. Kellogg’s 1923 The Natural Diet of Man [sic] offers an interesting perspective into the vegetarian/vegan movement of the United States 100 years ago.

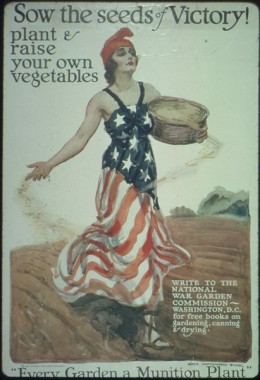

Take, for instance, the preface and final chapter in which Kellogg complains of the “meat” industry’s reaction to post-war declines in flesh consumption. As he explains, the industry launched an “Eat More Meat” campaign, flooding newspapers with scientific claims to “meat’s” essentialness to human health.

Take, also, the cringe-worthy examples Kellogg reprints in the chapter entitled, “Newspaper and Magazine Misinformation.” The “meat” industry has been bombarding the public with strategic advertising to increase profits for a century or more.

Despite this entrenching ideology, Kellogg seems confident the industry would not succeed:

The packers are certainly trying to “raise the wind” in behalf of their industry, but they will not succeed. When they set to work to find “scientific data wherewith to correct adverse propaganda,” they will find nothing to correct. The physiologists have been stating the simple, incontrovertible facts about meat, which show its uselessness and harmfulness, and there is not a word to be said in its favor which has not already been said and resaid so many times during the past that there is nothing new to say. […] it is not to be believed that these eminent and efficient promoters of national welfare can be persuaded by the packers to back up their “Eat More Meat” campaign, which has been organized, not in the interest of the public welfare, but simply to enrich the pocketbooks of breeders and butchers. (361)

What right have packers and breeders to undertake to exploit the consumers of food simply to create a market for their products? (362).

Despite this optimism, the role of “meat” in the project of oppression is deeply rooted and the “science” the industry creates is just as biased but convincing as it ever was. Kellogg, however, was witnessing the very formation of an ideology in an era of great social change. “Meat” was shaping nationhood.

Indeed, “meat”-eating and colonialism went hand-in-hand at this time. British colonizers, for example, explained their supremacy in India as a direct consequence of the physical and mental superiority granted from consuming flesh. Indians, who primarily ate plant-based diets, were argued to be weak, stupid, and ripe for subjugation.

This ethnocentrist and racist ideology permeated the Western defense of flesh consumption. Dr. Kellogg counters in The Natural Diet by highlighting many of the amazing and physically exerting feats that Indians regularly achieved. He suggests that any feebleness suffered by Indians and other colonized vegetarian groups was more accurately attributable to starvation. British imperialism, in other words, was the source of harm, not a vegetable diet.

Incidentally, Kellogg was certainly no egalitarian himself by any right. Notably, he founded a eugenics society at his Battle Creek sanitarium where he hosted conferences on “racial betterment.”

Photo from Willard Library.

While primarily concerned with “meat’s” impact on human health, Kellogg does make an ethical appeal to vegetarianism near the end of his book:

With winter’s frost an evil day arrives,–a day of massacre, of perfidy, of assassination and bloodshed. With knife and ax he turns upon his trusted friends,–the sheep that kissed his hand, the ox that plowed his field. The air is filled with shrieks and moans, with cries of terror and despair; the soil is wet with warm blood, and strewn with corpses (220).

As this prose attests, plant-based eating was serious business for Dr. Kellogg. He required vegetarianism of all patients sojourning in his Battle Creek Sanitarium. In fact, when patients were caught sneaking “steak,” he was known to place their meal under the microscope to grant them a closeup view of the bacteria active in the decomposing flesh. In a shock tactic that remains favored by vegan activists today, he hoped the exposure would repel and disgust them from further digression.

Perhaps understandable for the time, The Natural Diet of Man [sic] explicitly argues for vegetarianism, with only a fragmented acknowledgement of vegan politics. He does, however, note that a completely plant-based diet is just as healthful and nutritionally sufficient as a vegetarian one. It is also cheaper, he concedes. Kellogg even recommends nut milk, a suggestion would be unheard of in today’s corporatized and monopolized food system. That’s just as well. Today’s Kelloggs cereal is fortified with animal-derived Vitamin D. Nut milk or no, it would not suitable for vegans.

A version of this essay was originally published on The Academic Activist Vegan on May 25, 2013.

Readers can learn more about the politics of science and veganism in my 2016 publication, A Rational Approach to Animal Rights. Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.