Content Warning: Post discusses racism, sexism, and a number of other forms of discrimination, as well as the Nonhuman Animal rights movement’s protection of discriminatory attitudes and tactics.

This is a story about symbols and solidarity. It is also a pained confession of my sometimes uncomfortable identity as a white Southerner, one that I hope can constructively add to the dialogue. As I repeatedly come up against white fragility and hostility in the Nonhuman Animal Rights movement as it responds to coalition-building and diversity efforts, I felt compelled to share my thoughts here, born of both personal experience and research in social movement studies. If you have been directed to this essay or otherwise found yourself here and you are white-identified, I encourage you to read on with an open mind. I am not judging you, I am only imploring you.

I grew up in a small town in rural Virginia. The Confederate flag was constantly present in my life. Some people hang the flag on their porch. Lots of “good ol’ boys” plaster their trucks with them. My classmates regularly wore t-shirts featuring the flag to school. Civil War heritage is a major part of life in Virginia as well, probably because much if not most of the war was fought in our state. I am and always have been a history nerd, and I even participated in Civil War living history events and “reenactments” as a teenager.

In graduate school as a young woman, the flag came up in discussion in a sociology theory class. The professor was using it as an example of how symbols become socially constructed and can hold different meanings. He asked us who in the room was not offended by the flag. I am embarrassed to say, I was the only one that raised my hand. I was also the only person from a rural and poor background in the class (poor people where I come from don’t often make it to college, and they rarely find their way into graduate school). I was acutely aware of that. When “outsiders” criticize the confederate flag, some whites interpret this as another attack on poor, working-class Southerners who, to be fair, are disproportionately burdened by a substantial amount of structural classism. Race, of course, still matters, but it is conveniently erased from the framework.

I believe I said something along those very cliche lines of, “It doesn’t mean what you think it means. I don’t see it as racist.” Then I made some awful comparison about the swastika, insisting that Hindus shouldn’t have to abandon the symbol just becomes some people think it’s racist. Oh and didn’t you know that some African Americans fought on the side of the South in the Civil War?

Yep.

That happened back in 2007 and I still remember it vividly because I am mortified by it. I thought I was being critical, but I was really just thinking about myself. It isn’t about me, though. It’s about how others are hurt by these symbols. It’s about the systems of oppression that are still ongoing, still disadvantaging, and still costing lives.

Deep down, Southerners are not ignorant of this meaning. We know it’s not just about Southern culture and working class pride. A few summers later, I was tubing the river in the area where I grew up. I got ahead of my group and while I waited on the banks for them to catch up, two older white men came up to me and started a conversation, having recognized me through their friendship with my late father. While we were shooting the breeze, one of them made an off-hand comment about how they used to have a rebel flag hanging up on a tree by the river entrance to “keep the n*****s away.” I was more or less a stranger to them, but I was white, which made them feel comfortable acknowledging the flag’s implicit meaning. Shocking how I once convinced myself that these racist symbols could ever be “colorblind,” or that my naive personal interpretation as a privileged white person could ever supersede the larger societal meaning.

I share this story because I learned from it, regret past attitudes, and wish I had not sided with self-interested defensiveness. I wish I had thought of others’ interpretations, not just my own. After all, I live in a society, not a bubble. As Black Lives Matter dominates headlines and protesters fill the streets, there has been renewed contention over the flag’s use, which has, in turn, inspired white defensiveness and counter-mobilization. For whites, the contention is a symbolic attack on their way of life (and, whether or not they are willing to admit it, their privilege). For African Americans and other people of color, it’s an attack on their very right to life and safety. The two are not comparable.

The flag is just one of many examples where meaning is contested and racial inequality runs the risk of erasure. In my observations of the vegan movement, I have seen race issues ignored altogether, silenced by white gatekeepers, or derailed with appeals to Nonhuman Animal lives. Beyond the excuses (“We have to focus!” “Animals are suffering more!”), much of the resistance has to do with activists taking personal offense when their approach is criticized: “I’m not racist! This tactic doesn’t make me racist!” “This has nothing to do with violence against women!” “Speciesism is just like the Holocaust; that’s how it really is!” etc.

Here’s the thing:

When activists engage tactics that simulate the rape of women or disseminate images and sounds of cows being raped as a scare tactic, the movement appears sexist and callous.

When white activists publish cookbooks from an imagined stereotypical “thug” perspective, and keep pushing the book despite the protests of people hurt by these stereotypes, the movement appears racist and callous.

When middle-to-upper class (even millionaire) activists insist over and over that veganism is “easy” when, for so many living under structural oppression, it absolutely is not easy, the movement appears classist, racist, and callous.

When cis-gender activists belittle transgender persons who advocate for transgender rights instead of prioritizing speciesism, the movement appears trans-antagonistic and callous.

When thin-privileged activists politicize obesity and post billboards mocking women of size by calling them “whales” with the intention of shaming them toward veganism, the movement appears sizeist and callous.

Who would want to associate with such a movement? If participants are attracted by racist, sexist, classist, or sizeist claimsmaking of this kind, are they associates the movement will benefit from? Are these the best ambassadors for a social justice movement?

Importantly, many vegans engaging these problematic tactics have been exposed to patient explanations from people who are actually living under the oppressions themselves. Yet, vegans continue to defend these tactics with gusto, doubling down on defensiveness. In retaliation, it is vegan feminists and allies who are accused of bigotry, taking things too seriously, or looking to start trouble and drama. I am reminded of a small protest that took place at the Animal Rights National Conference in 2016 in which an audience member took his turn during the Q&A to ask the white male speaker to consider not taking up so much space at conferences to make room for marginalized voices who are rarely given platform. The moderator shut down the protester, and the audience erupted in applause. They were not clapping in support of the protester’s brave actions, but rather the moderator’s restoration of (white supremacist) order.

Defensiveness over mindfulness.

Me-myself-and-I thinking subjected me to public embarrassment in that graduate classroom so many years ago, and I have learned a very important lesson since that day. Activism isn’t about one’s own interpretation. Given that the Nonhuman Animal rights movement is largely white-identified and middle-class, the prevailing interpretations can never be considered universal. A failure to acknowledge privilege equates to a failure in resonance. Activists must consider the interpretation of those who are being hurt by movement rhetoric, attitudes, and behavior.

There are consequences resulting from this ignorance. If the goal is to grow the movement, shouldn’t activists be more concerned with the interpretations of others rather than their own? After all, resonating with the audience is one of the most important goals for any social movement.

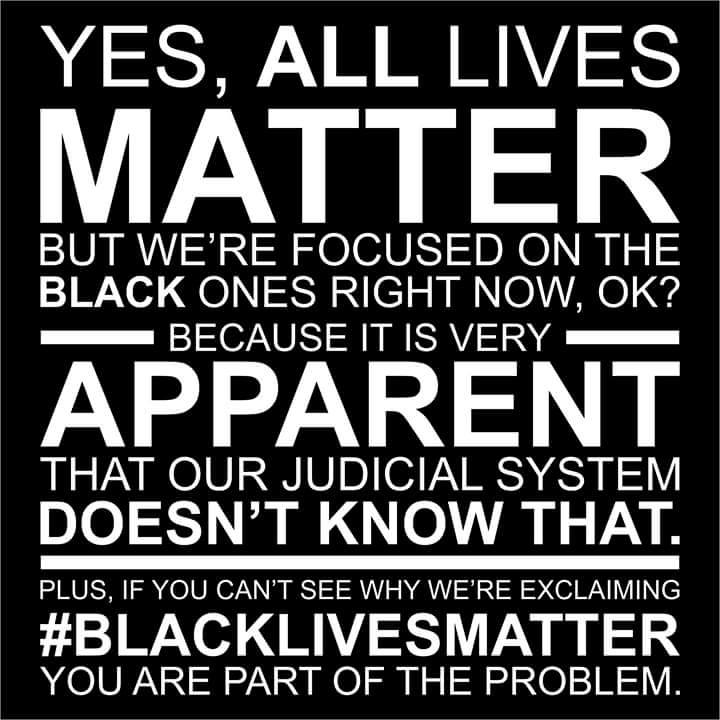

Ethics matter as much as efficacy, however. Defensiveness over white privilege runs counter to the ethical position the Nonhuman Animal rights movement espouses. The white supremacist hijacking of symbols in an effort to racially neutralize them for the interests of privilege is not in alignment with justice. “All lives matter” claimsmaking, for instance, is frequently cited by white vegans who perhaps wish to capitalize on the visibility of Black Lives Matter mobilization to draw attention to other animals who are also suffering extreme violence. Black Lives Matter claimsmaking, however, is not race-neutral, and when whites attempt to make it so, this is an act of racism.

“All Lives Matter” is not alliance-building, it’s alliance-destroying. It suggests that mobilization to improve the life chances and well-being of the Black community is somehow unwarranted or distracting. It erases difference, and when difference goes invisible, this invisibility supports systems of inequality that feed on difference. Difference exists whether or not whites choose to acknowledge it, and rejecting its existence is complacency with oppression. Nor should readers forget the Nonhuman Animal rights movement’s historical legacy of racism. Appropriating the symbols of Black liberation when the movement has, for years, both excluded and oppressed Black persons is especially problematic.

All lives can’t matter until Black lives matter. Espousing that Black lives matter does not mean that Nonhuman Animals do not matter, or that white lives do not matter, or that anyone else’s lives do not matter. It only means that the systemic oppression faced by Blacks is abominable and must stop. White vegans have an obligation to support this effort, not to derail it.

White vegans, it’s not about you.

A version of this essay was originally published on The Academic Activist Vegan on July 15, 2015.

Readers can learn more about the legacy of racism in vegan advocacy and the importance of a pro-intersectional approach in my 2016 publication, A Rational Approach to Animal Rights. Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.